Swimming Technique

Like treading water, swimming is not a problem that can be solved with sheer physical effort. Your speed and endurance in the water is heavily dependent on your technical skill. As such, swimming programming for special operations selection training should focus on skill development, with fitness coming as a byproduct of that training.

If you use swimming as a means of conditioning without considering the technique you’re developing and reinforcing along the way, you’ll only become good at swimming poorly. That’s about as effective as putting a bigger engine into a car with flat tires.

Preparation for SOF selection requires a huge base of submax aerobic capacity – working away for hours and hours with your heart rate in zone 2 or the low end of zone 3 (or in the 130-ish range for most people). It’s much more effective if you can spend that aerobic training time doing something productive and dynamic rather than slogging away on a hamster wheel. Swim practice is a great way to do that. If you focus on the motor patterns necessary for efficient swimming, the physiological adaptations will follow.

First eliminate drag, then create power.

There are two aspects to swimming speed and endurance: drag and power. For most people, drag is far more of a limiting factor than power, and until your drag is minimized and you’re able to efficiently glide through the water, the amount of power you can express won’t really matter. It’s kind of like breath-holding – it’s only helpful to tolerate CO2 well if you can stay relaxed and not burn through your oxygen in 20 seconds. Efficiency comes first.

Efficiency Step 1. Small hole

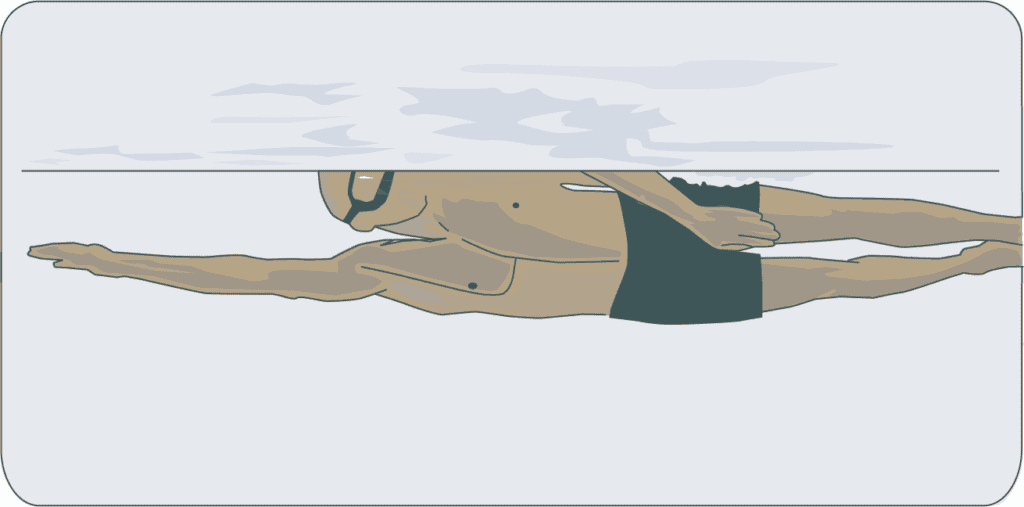

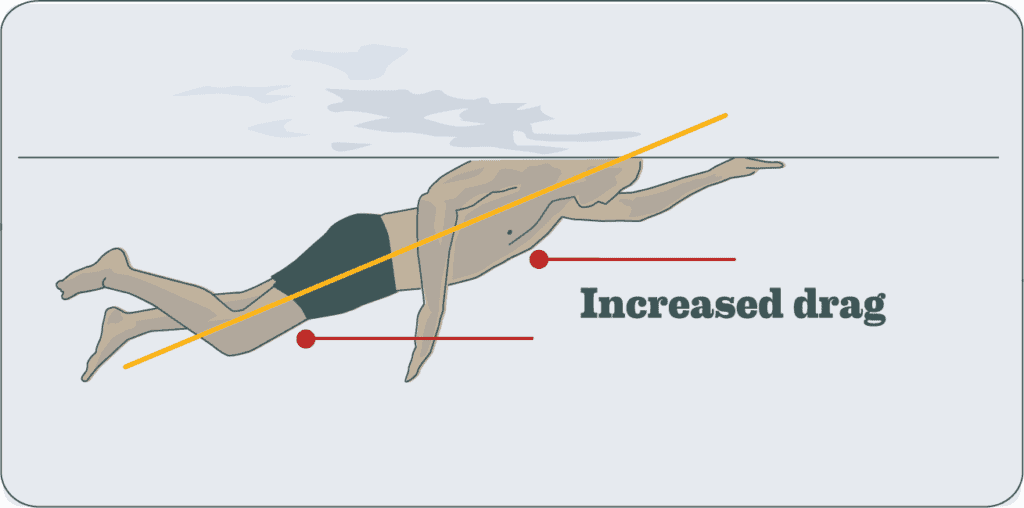

A good cue to think of is to make your body like a pencil moving through the water. Think of the difference between holding a pencil perpendicular to a piece of paper and punching it through compared to holding the pencil flat against the paper and then pushing it through. You want to make the smallest “hole” in the water as possible.

This means that learning to balance your body to stay horizontal in the water is extremely important. The combat sidestroke makes it especially easy to unknowingly drop your legs and feet lower than the rest of your body and angle your body downward, which substantially increases drag.

There are many different drills that can help you to learn this, as well as the streamlining concepts described next. We strongly recommend that you check out Total Immersion coaching for in-depth courses, video examples, and TI-certified coaches.

Efficiency Step 2. Stay long

At a given volume, longer objects have less drag in the water. A key part of swimming efficiently is learning how to stay stretched out and streamlined in the water by keeping one arm stretched out in front of you for as much of the stroke as possible while your hips generate propulsion and your other arm provides a stabilizing force to help your hips.

Generating force

If you attempt to solve problems in the water with sheer effort, the physics involved will quickly punish you. You’re probably familiar with the equation for calculating force from somewhere in high school: Force = Mass x Acceleration. If you try to move faster through the water by just paddling your arms or kicking your feet faster, it requires eight times (23) the effort (via acceleration) to double the amount of force you produce.

If, however, you increase the mass side of the equation and improve the propulsion generated by your entire body, starting with your hips, you can dramatically increase your force through the water without moving your arms or legs any faster. This is much more efficient.

Think of a fish swimming through the water. Its long, streamlined form moves fast and efficiently with a full-body movement that propels it forward. Nothing is wasted. Now imagine if instead of moving its body, the fish held rigidly still and tried to move forward by frantically paddling its fins, like a wind-up bathtub toy. Lots of motion, not much progress.

As silly as it sounds, this flailing-limbs-on-a-rigid-body method is how many people start out trying to swim. It’s not terribly intuitive, but good swimmers move through the water more like fish than like paddling ducks or dogs.

Whereas fish use their full body in a rhythmic side-to-side motion, good human swimmers in a freestyle or combat sidestroke manage somewhat the same effect by using their body to generate rotational force, starting with the hips. Just as with a boxer throwing a punch, a batter hitting a baseball, or a breacher knocking down a door, powerful, efficient propulsion in the water starts at the hips. The arms and legs transfer this force, more so than generate it.

Your hands, feet, and arms should only contribute a small amount to the overall propulsive force that moves you through the water. With efficient swimming, your hands don’t really move water, it’s more like they’re anchors that “grip” the water as you pull your body along. Arms and hands help to stabilize your body and counterbalance the force generated by your hips, so that you can use full-body propulsion.

Training Methods

Swim training for special operations is so heavily slanted toward technique that there is not much need for intricately varied training protocols and nuanced energy system guidelines. Those sorts of things are more productively managed in the gym and on the track. In the pool, your primary goal should always be technical practice. The local muscular adaptations and energy systems needed to swim fast will come along for the ride if you do the work.

Thus, programming for swimming training sessions is mostly about volume. And, how much volume you can do each training session depends on how much time you have available and how much volume you can handle given your fitness level and technical skill.

Remember the principles of motor learning and stress inoculation. There’s no use adding stress to a skill that you haven’t mastered. Don’t beat yourself up in the water until you’re confident that you’re inducing metabolic stress with a motor pattern (your swim technique) that’s technically solid, efficient, and isn’t breaking down halfway through your workout due to fatigue or inattention. Only push your physiology in the water to the extent that your technique can keep up.

Stroke Golf

The fastest swimmers tend to use the fewest strokes for a given distance. They’re faster because they are more efficient, not because they generate more propulsion with each stroke. Instead, they get the most out of each ounce of energy expended through reduced drag.

With stroke golf, you’re simply playing a game to see how few strokes you can take on each lap across the pool. As with golf the lower the number the better.

Start by swimming a lap without paying too much attention or using any particular drills. Just swim. Count how many strokes it takes. From here, work to beat that number on each lap.

This can be a good way to assess your progress with technique improvements. For example, you could work on better head alignment, practicing keeping your head more in line with your torso rather than lifting it excessively and dipping your hips and legs lower in the water in the process. If that produces an improvement in your efficiency, you should notice a change in how many strokes it takes you to get across the pool.

This can also be used to measure the effectiveness of drills that inherently slow you down. For example, you can practice swimming with your hands closed in fists to reduce how much pull you can generate with your hands, highlight the importance of good elbow bend and a vertical forearm to create a propulsive surface, and force you to rely more on rotational full-body power. This should initially slow you down, but if you’re counting your strokes per lap, you’ll also have immediate feedback to let you know when you’re becoming more efficient with the drill.

Intervals

Like anything else in training, swim practice is ultimately about the extension of quality. You develop a good movement pattern and then you work to execute that movement faster or against greater resistance, for longer.

Using intervals in your swim training can be a way of managing energy systems demands. By adjusting intensity alongside work to rest ratios, you can manipulate peak and average heart rate during the session, and shift the predominant energy system being emphasized. But, as we discussed at the beginning of this section, it’s generally more effective to think of swim practice through the lens of skill acquisition, with only a secondary focus on the energy systems involved.

Thus, swim intervals are primarily a way to extend the distance for which you can maintain a given pace at a high level of quality.

For example, let’s say you can swim a 500-meter combat sidestroke in 10 minutes flat. That works out to two minutes per 100 meters when done continuously. You may be able to hold closer to a 1:45 pace for 100 meters if you swam that distance in isolation, which would be equivalent to an 8:45 500-meter swim if you could string those 100s together.

This is what you’re working on with intervals: through various changes in total volume, pacing, interval distance, and density (work to rest ratios) you’re gradually improving your ability to hold a given pace for a given distance. You can do this through a variety of different methods, such as:

- Progressively decrease rest

- Progressively increase the interval length

- Progressively increase the total volume

Continuous swimming protocols

Continuous pool workouts can be broken down into two categories:

- Intense, threshold-level, or test-pacing. Here, you’re working to test and improve the fastest pace that you can sustain for a given distance.

- Sustainable, submaximal, or efficiency-oriented pacing. Here, you’re working to improve the long-distance pace that you can make feel easy and sustainable.

These are both predominantly aerobic workouts, but they will emphasize different aspects of the aerobic system. The intense, maximally-paced swims will generally keep you close to your anaerobic threshold. The sustainably-paced swims will more in the zone 2 or 3 heart rate range (below about 150 bpm as a rough rule of thumb), which as we discuss in the energy systems chapter of our book will produce different cardiac and autonomic adaptations.

Long, maximal-effort swims also present an opportunity for mental skills development, in that you’ll often find yourself getting into your own head on these swims. Longer swims can take quite a long time, and there’s not much to think about or pay attention to aside from your own thoughts. You’ll be doing something intensely that will probably be at least mildly unpleasant the entire time, and the only way to make it stop – especially in the ocean – is to see it through and finish it. This presents some good opportunities to work on your self-talk and other mental skills strategies, as we cover in chapter 13 of our book.

With either of these methods, your primary form of progression is through volume. You do it well, and then you work to do it more.

Within those boundaries, there are some other more nuanced factors to be considered. For example, with submaximal-effort swimming, you can keep the pace fixed and work to decrease the amount of effort that a given distance costs you. You can also work to swim at a faster pace while keeping your effort fixed at easy and sustainable. As you become more efficient, you’ll be able to swim a given distance at a lower and lower cost. Eventually, your easy go-all-day pace will also be fast and competitive. These types of swims are also good places to work on subtle improvements in technique.

The progressions here look less technical than for intervals, although there are still complex things happening in the background as you work on mental skills and constant small technique adjustments. Progressions for continuous swimming are mainly based on progressing either volume or intensity/speed, or some mixture of both.

You don’t need space math

These examples show fluctuations in volume, intensity, or work density but in many cases you don’t need to change anything numerically from week to week. Swimming is so dependent on technical proficiency that you could put years into swimming the same distance, but better, with more efficient technique, and still make steady progress.